Have you ever built an Agile team, the very first in a large organisation? Or perhaps you’ve already taken part, or even just watched, full of hope for the changes it would bring?

The euphoria of the early days often comes up against the structure of the organisation, putting the brakes on the enthusiasm of the most willing and giving way to a certain weariness. But all hope is not lost! History will not repeat itself endlessly.

I’d like to share with you an experience of creating a Product team within a company that has historically been organised to carry out projects. We relied in particular on the concepts of Team Topologies to bring out the responsibility for the product, guarantee a strong decoupling from other products/services, and limit the cognitive load on the team.

Context#

A Swiss company in the energy sector, historically organised to carry out projects, decided to set up a multi-fluid remote reading platform (water, gas, electricity, heat) so that its customers could recover and thus reduce the energy consumption recorded on their meters.

Courageous decisions are being taken#

The time allowed to make this platform available to its customers is just 3 months, compared with the company’s average delivery time for this type of solution of 5 months. The company also wanted to take advantage of this new project to acquire expertise in the development of cloud-native solutions.

This meant thinking outside the box. To facilitate learning and experimentation, a multidisciplinary team was set up specifically for this project. This team was then able to put in place a working framework that encouraged empirical approaches. Authorisation to deviate from certain company rules was quickly granted. Weekly monitoring to management was introduced to remove the organisational constraints that the team would have to face. Everything was being put in place to give the team as much autonomy as possible and enable it to overcome the technical and organisational challenge.

Team composition#

- an electrical engineer, coordinating the installation of the sensors and stock management;

- a telecom engineer, in charge of data communication between the sensors and the web platform;

- three full stack .Net developers, in charge of developing the web platform;

- a DevOps engineer in charge of integrating and deploying the web platform on Azure;

- a software architect, to facilitate the design of the solution architecture;

- a product manager, responsible for the vision and strategy of the web platform.

Unfortunately, some members of this team could not be 100% dedicated. Fortunately, we were able to obtain from management :

- the limitation of the assignment of these people to a maximum of two projects, including our own;

- the ability to decide together which days we could work together.

Minimum Viable Product#

Uncertainty about how to deal with the constraints of development in the cloud and the 3-month deadline for delivering value to customers forced the team to focus on defining the ‘Minimum Viable Product’. The first task was therefore to identify the value stream, which made it possible to select the mandatory activities and identify the business services that could be reused without complexity for the team.

The team therefore decided :

- to build few operating tools, given the low volume of sensors to be managed initially (<100);

- to minimise work on the ergonomics of configuration management activities and adding sensors to the platform by only providing the service in the form of command lines;

- For the time being, all the complex integration issues with the company’s departments (management of orders and sensor stock) have been set aside.

As is often the case at the start of a project, the team thought that once all the difficult decisions had been taken and the contours of the product defined, the creation of the platform would just be a long, quiet river. It turned out to be quite the opposite…

Used to having an infrastructure available on its premises, the team paid no attention to the cost of its solution in the cloud. It was setting up multiple environments (dev, qual, prod) that ran all the time, with a large volume of data for which no constraints on their lifespan were taken into account.

Creating the ‘Device to cloud’ data flow was simple to implement. The opposite ‘Cloud to device’ flow was really problematic for the team.

A service interruption on the test sensors was caused by a poorly validated change to the database structure. This identified a gap in the definition of our requirements for operating the solution with confidence: the ability to replay past events.

Fortunately, to overcome these difficulties, the team was able to rely on:

- an empirical approach focused on value;

- a sense of solidarity and team spirit built up step by step;

- management that listens and is pro-active;

- a solution-oriented rather than a problem-oriented approach.

1st delivery to the customer#

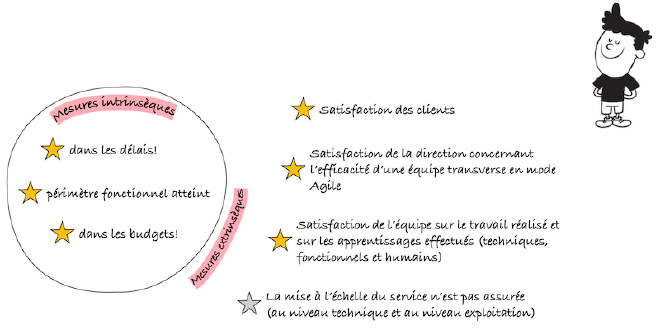

Traditionally, as with any project-oriented organisation, the team was assessed on its ability to achieve the intrinsic objectives, i.e. ‘on time’, ‘functional scope achieved’ and ‘within budget’. The team met these ‘classic’ objectives. However, it had also set itself other, extrinsic objectives, precursors of a product-oriented approach:

- customer satisfaction

- management satisfaction with the efficiency of a multi-skilled cross-functional team;

- the team’s satisfaction with the work carried out and the lessons learned (technical, functional and human);

- Scalability of the service offered by the platform (at both technical and operational levels).

Apart from this last point, all the team’s objectives have been met.

A service is born with new challenges#

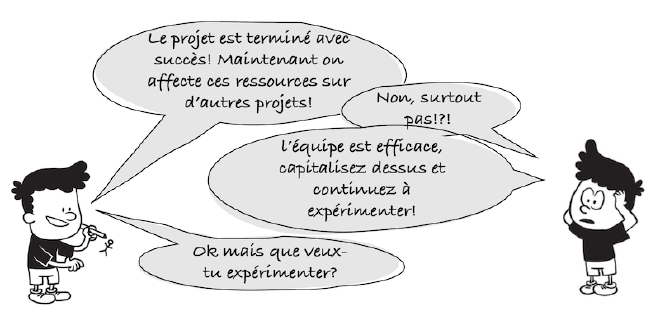

A project comes to an end. It’s time to break up the team so that staff can be assigned to other projects! How often have you seen this in project-oriented organisations? All too often in my case. Fortunately, as the management committee was closely monitoring the team and as the project was a real success, they quickly agreed to launch another experiment: ‘You build it, you run it!

An agreement was reached to keep a stable team for a year, financed 60% by the revenue it generated, with the remaining 40% to be found by the Product Manager and the sales teams. The team was now to develop and operate the platform.

Benefits of experimentation#

Without going into detail about all the experiments carried out with this team, at the end of just over two years’ work, here are the main benefits identified:

- an ability to pivot the product in response to changes in the company’s strategy

- an ability to keep the cost of the platform lean, thanks to a FinOps approach

- low technical debt

- optimised operating costs

- a significant reduction in the burden on managers of managing budgets and capacity schedules

Key success factors#

- Management that listens and is pro-active

- A willingness to experiment

- A multi-skilled team to facilitate decision-making

- An empirical approach to address complexity

- A structured product approach based on objectives

- Team topologies to define the product’s contours and facilitate interaction with other teams.